A Still Life is a Real Life

The video portraits can be seen in the three traditional ways that artists construct space. If I hold my hand in front of my face, I can say it is a portrait. If I see my hand at a distance, I can say it is part of a still life, and if I see it from across the street, I can say that it is part of a landscape.

In constructing these spaces, we see an image which can be thought of as a portrait. If we look carefully, this still life is a real life. And in a way, if we think about it and look at them long enough, the mental spaces become mental landscapes.

These portraits stem from a work I did in the 1970s, VIDEO 50. I made various portraits, including surrealist writer Louis Aragon, socialite Helene Rochas, a duck, a priest I met in a bar, museum director Pontus Hulten, Sony CEO Akito Morita and France's Minister of Culture Michel Guy. Those portraits could be seen on TV, in galleries, museums, subways, hotel lobbies, airports, or even on the face of a wristwatch.

I imagine the VOOM portraits being seen in public spaces, as well as at home. At home, they are a kind of window in the room or a fire in the fireplace.

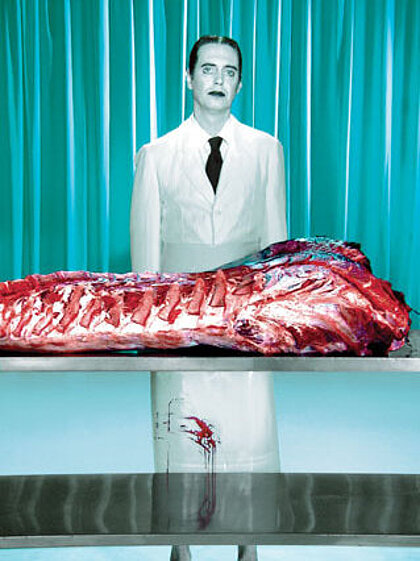

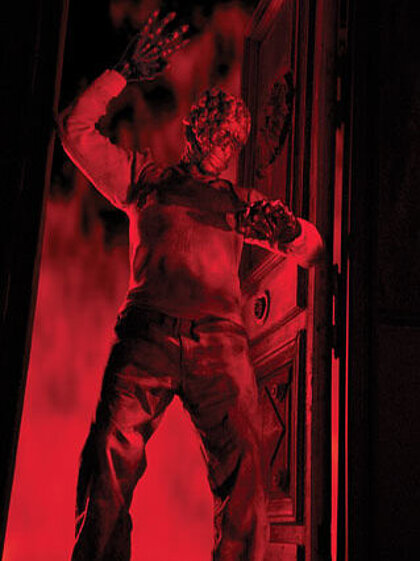

Often people ask me, "What are the ideas behind the images?" I do not interpret my work. Interpretation is for others. To fix a meaning to a work limits its poetry and the possibility of other ideas. They are personal, poetic statements of different personalities.

A man from the street, an animal, a child, superstars, gods of our time. (Robert Wilson)

VOOM Portraits:

Commissioned and produced by VOOM HD

Robert Wilson created his first portraits of distinguished figures such as Louis Aragon, Pontus Hultén and Helene Rochas, as well as those of unknown passers-by and animals, in the 1970s. Although Wilson himself refuses to interpret his works, it is clear that he willingly takes on the task of interpretation when such figures are concerned. His portraits are namely theatrical productions and hence interpretations. Robert Wilson's artistry is made up of a series of singular personal experiences of abnormal behaviour (such as speech impediment or deafness), as well as of the key artistic impulses of the 1960s (from Performance through to Minimal Art), which left their mark on his era-defining, legendary productions from the 1970s onwards: 1976 Einstein on the Beach with music by Philip Glass; 1979 Death Destruction & Detroit with music by Alan Lloyd; 1981-1984 The CIVIL warS, a theatre project with productions from five countries that was intended for the "Cultural Olympics" Los Angeles in 1984 (unfinished). He worked with William Burroughs and Tom Waits (The Black Rider, 1990), with Laurie Anderson, David Byrne, Lou Reed (Time Rocker, 1996) and others. Later on he also staged classical pieces with contemporary writers with whom he was friends, such as Heiner Müller and Susan Sontag. Out of his stage art he also became a stage designer and sculptor, painter and illustrator. His pictorial art was not, however, just confined to the surface; he also created three-dimensional objects, installations and environments of the highest poetic order - partly absurd and surreal, partly extremely minimalistic, but always surprising. In the time-based picture form of video and film, he attained an innovative pictorial language that created a world somewhere between the Chaplinesque and the Kafkaesque but that was always Wilson. More recently he has passed on the wealth of his theatre language to museums and, as an outstanding curator, has created new types of exhibitions and ways of presenting objects. All his experiences as an artist of pictures and of objects, as a stage designer and director, as a choreographer and a curator have been concentrated in his video portraits since 2004, because the technical potential of high-definition television allows him to diversify further his wealth of pictorial and stage language: movement, gesture, make-up, costume, scenery, as well as the styles of high and popular culture, and classical as well as new media: painting, design, music, opera, dance, theatre, photography, television, film, etc. The personalities represented in the portraits refer, in doing so, not only to their own biographical details but also to cultural-historical sources. The subjects are thereby both constructed and authentic, both biographical and sociographical, and portraits of their lives as well as of a medium or an era. The portraits are visual history but also part of history, or rather, history themselves. Robert Wilson creates portraits not only of famous figures but also of unknown people and animals which until now were not represented artistically. It is precisely in their production that Wilson's complex pictorial and tonal language reaches its apogee, namely, a celebration of empathy. The anonymous become divas; the neutral achieve cult status. Wilson's VOOM portraits thus have a cognitive function. In the history of portrait painting and of photographic portraits, particularly of staged photography, his staged portraits are not only the pinnacle of achievement but also represent, above all, a climax that is ground breaking. (Peter Weibel)