The Neue Galerie Graz has pursued a policy of presenting its extensive collection of 19th and early 20th century works in exhibitions with a thematic focus for some years now: the two exhibitions "Unter freiem Himmel" - "Under an Open Sky" - (2000, Neue Galerie) and "Natur im Bild" - "Images of Nature" - (2003, Schloss Stainz) dealt with aspects of Austrian landscape painting, "Die Welt der stillen Dinge" - "The World of Objects" (2004, Schloss Herberstein) was dedicated to the still life. "Von Waldmüller bis Schiele" - "From Waldmüller to Schiele" (2001 till 2003 in Schloss Eggenberg) offered a selection of the master works from the Neuen Galerie collection. From Autumn 2006 genre painting, one of the most popular art forms of the 19th century, is being considered extensively in a long-term exhibition. Some 150 works of the period are on show together with a number of 17th and 18th century paintings, provided in cooperation by the Alte Galerie Graz. This exhibition thus provides an overview of around 400 years of genre painting and attempts to trace its development through these selected examples. This would appear to be a particularly worthwhile task at the present moment and in relation to the realistic painting of the past few years in which a younger generation of artists are again turning to everyday subjects and dealing with the taste of the times, to examine this art form in a wider context of time. Parallel to this we are also presenting a trivial cinema season (e. g. horror, crime, western films) of films that share a similar disregard to that also shown to genre painting, but which nevertheless provide more substantial statements on social reality than other far more highly valued film types.

Genre painting experienced a first flowering in Dutch 17th art; in the 19th century it advanced to become the most important form of painting together with the landscape. The rise of both forms was closely linked to the characteristics of middle class structures, which provided a sustained support for the development of realistic tendencies in art. Until this time it had been largely Biblical and mythological themes or significant historical events that had been considered worthy of immortality in painting, not least as a means of supporting the social supremacy of the nobility and the church. The public for genre painting, however, came from the economically upward mobile and self-confident middle classes, whose social dominance began inexorably to overcome the traditional order. Art reflected this process through its decisive interest in a present so thoroughly familiar to its attentive public. Subjects of everyday life in an urban and a rural setting formed the central circle of motifs. These are the transitory scenes of life of which Schopenhauer said that they represented the "depth in the understanding of the idea of humanity" and which had attracted increased attention from the beginning of he 19th century.

Despite this epoch making historic change in values that was not least a major influence on the continued development of art, the illusion should on no account be harboured that genre painting was a precise representation of daily life - at least not in the early part of the 19th century - nor as if it had taken over the role of photography and had frozen human activity in a snapshot perspective. The common ground shared by literature and painting presents a similar situation: the artists were not chroniclers in the standard meaning of the term, they were narrators. They found their subjects in reality, but only to submit this to an aesthetic transformation, an approach with a poetic license and by this means to make statements of general validity. These pictures not only provide insights into private life, they also produce - class typical - everyday situations. Accounts of the everyday life of the people, their happiness and their despair, the imaginations of the painters themselves had their roots in the final analysis in joy and sorrow. The sentimentality of the scenes that sometimes appears exaggerated is a consciously calculated factor. This typical ambivalence between ideal and reality in early genre painting here follows in the footsteps of the art of an earlier period with its religious, mythological or historic subjects, since like these it also appeals to the ethical consciousness of its audience.

Two directions can be observed in the course of 19th century genre painting: parallel to the progressive trend of thought in the period marked by the natural sciences as also critical reflection on the own environment in the train of historical studies the artistic perspective is on the one hand more "documentary" with greater emphasis on facts. On the other hand the classical narrative strategies of the genres lead to an effective and emotionally charged intensification. Various plot strands are woven in the process into "anecdotal" genre paintings, a pictorial form that was developed to the embodiment of later genre painting. The scenes presented are equally sections of a longer narrative, developing a temporal prefix and suffix for the observer from an abundance of motif details. Genre painting confronted the historic picture on terms of equality, a fact clearly evident in the monumental forms that were favoured.

Art experienced a clearly apparent turning away from the positivist euphoria of the previous decades in around 1900. The "end of naturalism" was proclaimed (Hermann Bahr), the naturalism which with its relentless depiction of reality had presented the tragedy of secularised mankind in its full magnitude. The aesthetes at the turn of the century were convinced that the progress of culture was rooted purely in an increase of earthly beauty and the inter-penetration of art and life, in accordance with which principle the aestheticising of life was accompanied by an ethic sublimation of humanity. The problems of the times were clearly defined, however, and artists, writers and intellectuals in particular strove to counter suppression, while also demanding a specific form of aesthetic permutation. The art of the period around 1900 is concerned with the essential, the essence of mankind and the relationship of humanity to the "world in its entirety" yet it nevertheless reveals a longing for beauty and harmony. It seeks paths aside from the track of sober causality, attempting to force its way into spheres which withdraw from and must revoke the methods of the modern natural sciences.

In the course of the modern movement and within the framework of the academic discipline of art, which was under obligation to the notion of "progress" in art, where the course of painting was traditionally traced from the development of the ideal, through illusionist directions down to abstraction and concrete art, genre painting was regarded as a dimension in the occurrences of art that could well be neglected. Nevertheless genre-like motifs continue to recur in the painting of the 20th century, although first and foremost with the aim of examining the problem posing that is immanent in art itself. The relationship to the objective played a significant role in the German speaking countries in particular, where a concrete art was never truly able to gain acceptance on a broad front. Expressionism sought to capture the human being psychologically, the artists of the New Objectivism were no less interested in fathoming out the nature of things - and of human beings - and simultaneously to turn their attention to the political and social phenomena of the period. It is no longer appropriate to speak of genre painting in the accepted sense in the case of these works, since art has developed its own language of symbols the statements of which are not only made through things and narrative strands, but largely through chromatic and formal implications.

Classic motifs, such as harvest scenes for example, or the general depiction of farmers were, however, to find a continuation. The persistence of the tradition after 1918 and its revival in the 1930s was also a significant factor in the collective search for an identity following the collapse of empires in the economic and political turmoil of the years between the world wars and the strengthening again of a declamatory notion of nationalism in the train of Nazi ideologies. While subjects of this kind contain a by no means insignificant potential for conflict after 1945 on account of their former political reception - the discourse in Austria is well known - they were the expression of a new start in the post war years and the reflection on ideas with a timeless significance.

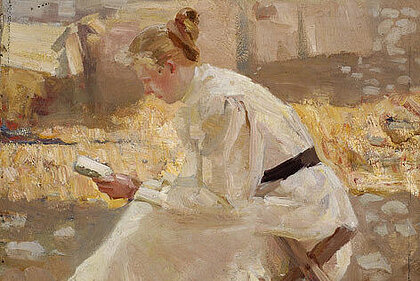

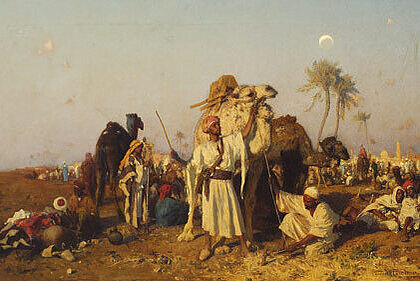

The exhibition attempts to record the development and structures of genre painting on the basis of the following categories. "Moving Moments" (room 1) marking the beginnings and also dominating genre painting of the early 19th century. "Examples" (room 2), it was above all the Dutch painting of the 17th century that provided a source of inspiration here as is also clearly illustrated in "Place of Conviviality" (room 3). The "Imagination of the Past" (room 4) was the principle intention in historicism. "Military Scenes" (room 5) was a very readily chosen subject since it offered opportunities for an effective augmentation of the emotional. Country Life (room 5) served as a projection screen par excellence for middle class notions of the idyllic, providing a location for the longings of the city dweller. Home life is one of the main areas examined by genre painting. It is the location where the "Family" and moments of "Leisure and Meditation" occur and are developed (both in room 6). "Religiosity" (room 6) played a decisive role in the lands of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in particular and was a frequently treated subject. "Modern Life" (room 7) records the city as the culmination point in society, reflecting the demographic changes of the period. "Overseas" (room 8) reviews the exotic locations of genre painting: It is here that fascination with life in the south finds its expression - from realistic presentation to scenes of imaginary opulence.