“Resistance is not wanting to live in the limited imagination of the white colonial mind.”

Céline Semaan Vernon, Lebanese-Canadian artist and advocate

When my grandfather died, the only thing I took with me from the house was a small wooden frame which had always hung above his desk in the living room. In the frame there is a newspaper clipping with a photo of a man in a suit on it. He is nonchalantly holding his head between his two interlinked hands resting on his neck and sort of resembles my grandfather. Underneath the newspaper scrap is the end of a letter that reads “Very kind regards, Marshall McLuhan”. To this day I am not sure why exactly I felt like this was the one piece I chose to remember my grandfather by, but here it hangs in my living room as I write these lines. As if keeping watch, its presence never fails to have a reassuring effect on me - my very own house ghost perhaps?

I presume I had heard the familial anecdote before, but most likely at an age in my life when Marshall McLuhan or media theory didn’t really mean much to me. Only much later, when McLuhan kept making appearances in diverse texts and readings, I came to realize what a truly beautiful and bizarre coincidence it was that out of all people my grandfather, a professor from a tiny mountain village in Austria, married, father of five, accordion player and model train enthusiast, was asked to translate McLuhan’s ‘Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man’ by a German publishing house.

Quoting Emily Dickinson and sitting at his typewriter my grandfather writes “Dear Professor McLuhan, ‘If there is no frigate like a book’, yours is the most interesting racing-boat I have come across”. He then goes on to ask for clarification regarding some details in the English original such as a lecture on ‘The Writer in the Electric Age’. To this McLuhan replies “there was never any script. I used a few headings and discussed the writer as a maker of anti-environments. The environments generated by each technology are themselves invisible, except to the artist. What ordinary people see is the old environment, the new one acting as a rear-view mirror only. The responsibility of the artist then is to reveal the new environment in the present since it is inaccessible to direct human perception” before sharing his home address to allow them for ‘faster’ communication.

As fascinating as it is to read their communication, as well as the snarky comments of others involved (for instance Swiss English literature professor Dr. Max Nänny confiding in his friend Marshall “I have read through Dr. Amann’s translation of UM and we have harmonized our terminologies, that is to say, he took over my suggestions”) - what is most surprising to me is my grandfather’s translation of ‘Understanding Media’ - a title which in English sounds rather technical if not manual-like into its whimsical German version ‘Die Magischen Kanäle’. Which in turn reverse translated might be something like ‘The Magical Channels’ (an interpretation deemed lurid and sensationalist in a footnote by the German translator of a collection of Umberto Eco essays - a fact my grandfather found quite amusing if not flattering). This free-spirited interpretation instead of a strict translation and the rather supernatural, metaphysical perhaps even esoteric connotations it lends to it - are not exactly adjectives or qualities I can easily reconcile with the image I have of my grandfather. In my memory a stern, silent yet kind and generous man, that aged 16 had been forced to go to war, who together with a few countrymen managed to escape from a prisoners’ transport of the Yugoslavian partisans and was - to his great luck - captured by the English, where he in fact began his career as a translator, while prisoner of war.

So, what could these magical channels be about? Considering McLuhan’s key thoughts in his media theory on how pervasive media and technology are on society, how in his eyes new media created a global village of unprecedented interconnectedness, collapsing time and space, producing new forms of organization and interaction, challenging linear and hierarchical forms of thinking while focusing on the fluidity of meaning and the constructed nature of reality, technology would most certainly appear magical to most. Magical as in almost supernatural, enchanting and extraordinary. And while McLuhan was mostly speaking about television - yes, television - at that time, he could not have anticipated the meteoric rise of the internet, social media, artificial intelligence or large language models and their full integration into our lives - yet still many of McLuhan’s thoughts hold up in relation to the ways that new media have shaped our human experience. And what my grandfather could not have known is that technology has advanced to a state where we do not even know how it works anymore - and by ‘we’ I do not only mean us mere mortals but also those developing these models.

So, when we ask chatGPT to explain McLuhan’s ideas of the ‘rearview mirror’ to us or we prompt an AI to create an image of a man playing the accordion on a racing boat in the Austrian Alps, we input this information into a truly miraculous blackbox and the output will certainly be delivered through magical channels. All these models have been trained by vast data sets scraped from the internet, hence not only having learned sexist and racist bias for instance but have also begun ‘hallucinating’, meaning that they also generate inaccurate or even fabricated information. These errors stem from data limitations, pattern recognition issues, and context handling challenges that these models face. In any case, it is remarkable that for McLuhan it can only be the figure of the artist who reveals these ‘magical’ environments – under whose spell ordinary people are – by means of creating anti-environments encouraging awareness, critical analysis and a deeper understanding of cultural and social changes.

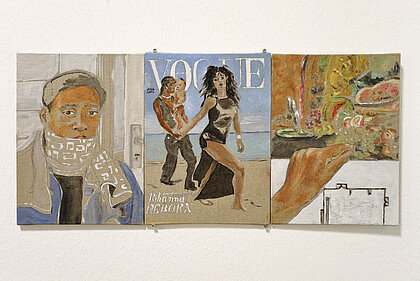

Sharif Baruwa’s dense yet precise, playful yet deep and nonchalant yet always carefully arranged environments seem to achieve both. They maintain a certain eeriness and opaqueness while revealing cracks and layers that allow for readings of the artist’s experience and cosmovision as well as the sociopolitical underlying structures that shape them. These readings are not fixed though, and as one moves through space, the singular elements appear to have an iridescence of a conceptual nature, meaning that as the visual connections between them change also their readings may vary.

The found materials usually employed by the artist could be said to be humble in their nature. Most of them have been previously used, discarded and then thoughtfully reworked and rearranged, achieving a meticulous balance between happenstance and intent. Here, coincidence and encounter are deployed rigorously as an artistic strategy. The fact that they have had some use before, gives them weight, alludes to stories and suggests identities. These materials and objects think and speak to each other, they demand attention, but they also invite experimentation of thoughts and sensations.

Effortlessly assembling drawing, painting, sculpture, collage, video and poetry into a fragmentary unity, Sharif’s environments provoke feelings of familiarity as they integrate not only materials but also objects present in everyday life. The techniques, as well as their level of precision differ according to necessity, varying from hyper realistic and detailed moments to less defined representations which at times only demand a few strokes to achieve a certain image or effect. At the same time, painterly and sculptural deliberations such as composition, proportions, combinations of materials or specific colour palettes are never neglected and put into the service of concept and content.

The stories, histories and characters inhabiting Sharif’s worlds range from the very personal, for instance family members to intriguing chance encounters with strangers. The power of these personal encounters is that they share a certain sensitivity and complicity both, with the viewer and the artist. Simultaneously, they serve to uncover underlying structural concerns and oppressive mechanisms that are at play in society. Sharif’s practice speaks from a position of loving resistance to the logics and forces of oppression that have led us to a moment in time where gruesome crimes against humanity are committed overtly and with impunity on the stage of world politics and it has become impossible to ignore the endless trail of broken promises.

It is of the essence to understand that these forms of oppression, such as racism for instance, do not merely occur out of plain ignorance, lack of education or imagined survival mechanisms based on the shaky grounds of biology but that they have been care- and masterfully inculcated in a longstanding process that began with the division of the world between the 15th and the 19th century through European imperialism and colonization. In ‘Critique of Black Reason’ Achille Mbembe delineates how, in what could be described as a schizophrenic move, European political and philosophical thinking achieved to reconcile despotic governance beyond its national borders and responsible representative governance within. Race made it possible to classify human beings in distinct categories and bureaucracy emerged as a tool of domination linking death and commerce. The Other, the native, was not seen as human in the same way which made the ‘world-outside’ a zone outside humanity: a space of unrestricted conflict, open to free competition and free exploitation.

The complexity and heterogeneity of the colonial experience cannot be emphasized enough, yet the racial signifier was of a constitutive nature. Therefore, the colonizing nations had to ensure the education of a racist subject. Psychoanthropological principles and theories of the inequality among races laid the foundation for a system of classification, validated through practices of eugenics and enabling the formation of a racist consciousness that not only heralded a new age of virility, but also allowed for the renewal of national energy at the same time legitimizing and promoting the imperial project of the so called ‘Western civilization’. A pedagogy aimed to habituate people to racism operated for generations and racial difference was normalized within mass culture through the establishment of institutions such as the museum, advertisement, literature or art.

We have seen how the principle of race can effectively be used to stigmatize and exclude, to segregate and isolate, or even eliminate a particular human group. So how to undo all these masterfully orchestrated and deeply embedded logics of race? How to deconstruct these deadly systems and cultivate ways of understanding that we have not nothing but everything in common? Or asked differently and quoting Egyptian filmmaker Youssef Chahine ‘Do you know how to love? Do you know how to care? That is civilization’.