The exhibition Poetics of Power highlights the complicated and ambiguous nature of power, which is omnipresent and constantly reproducible in the shaping of interpersonal, cultural, national and economic dynamics. It aims to reveal manifestations of power that are hidden in symbols, gestures and often unquestioned in existing relationships or systems. At the same time, it also explores their poetic nature by recognising their omnipresent influence and ambivalence.

Poetics of Power

Image Credits

asymmetry of power

Poetics of Power focuses on several thematic areas that cannot be clearly separated from one another. The exhibited works encompass various media, including photography, video, sculpture and installation. Works that speak of debilitation and colonial exploitation simultaneously postulate resistance and hope. Against the backdrop of numerous wars and conflicts, the exhibition also includes works that deal with feelings of helplessness or even resignation. But it is also about courage and solidarity as well as the need for responsibility. Even if most of the works relate to specific social situations or conflicts, the exhibition is primarily concerned with reminding us and reminding us that no power relationship, no asymmetry of power, is final or should be accepted as such. Poetics of Power is thus a call to engage with the decoding and unveiling of hidden or seemingly unquestionable socio-political contexts through the artistic positions on display.

Yael Bartana . Vajiko Chachkhiani . Jošt Franko . Gabriela Golder . Cristian Inostroza . Grada Kilomba . Daria Koltsova . Goshka Macuga . Daniela Ortiz . Ahmet Öğüt . Erkan Özgen . Hannes Priesch . Monira al Qadiri . Zanny Begg und Oliver Ressler . Anna Zvyagintseva . Lukas Marxt . Ala Savashevich

Show all

Works in the Exhibition

Image Credits

Yael Bartana

Two Minutes to Midnight, 2021

One channel video and sound installation (HD, colour), 47’. Courtesy of Capitain Petzel Gallery, Berlin; Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam; Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv; Galleria Rafaella Cortese, Milan and Petzel Gallery, New York

Two Minutes to Midnight is set at a round negotiating table where an all-female government of a fictional country is confronted with imminent nuclear threat from a foreign nation and its president ‘Twittler’. Fictional characters and real experts from the fields of defence, law, politics, theory and psychology negotiate in a democratic ‘peace room’ whether or not the use of nuclear weapons for their own protection can be authorised. The peace room is a reference to the toxic masculine ‘war room’ in Stanley Kubrick’s film satire Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Love the Bomb (1964). The complex debate revolves around the question of how to pursue a policy of disarmament and peace when faced with an acute threat and autocratic political pressure.

The documentary film material included in the work consists of recordings of the live performance What if women ruled the world? in Aarhus (2017) and Berlin (2018) and the performance Bury Our Weapons, Not Our Bodies! in Philadelphia (2019).

In Two Minutes to Midnight, Yael Bartana combines an analysis of geopolitical power games with the discourse on power hegemonies that are still dominated by men. She poses the question of whether a female-dominated political system would make different, more peaceful decisions.

The title of the work refers to the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: a symbolic clock that indicates the risk of a global catastrophe. The clock was set to two minutes to midnight in 2021; in 2024 we are at 90 seconds.

Image Credits

Vajiko Chachkhiani

Lower Than the Sky, 2021

Single channel video (2K, colour, sound), 16'25". Courtesy of the artist & SCAI The Bathhouse, Tokyo; White Space, Beijing

Lower Than the Sky shows a pink sky over a sea on which two boats are moving. As they draw closer we can make out people on board. However, shortly before they reach their apparent destination, the boats turn around. The passengers look directly into the camera and maintain eye contact throughout.

The film is a visual-poetic video installation about people who are forced to leave their homes. It was created in 2012, before the issue of refugees became a global, media-fuelled political issue. The topic of internally displaced persons has, however, long been familiar to the artist and in Georgia, which has experienced several territorial conflicts since the 1990s.

Despite their serious subject matter, Vajiko Chachkhiani’s video works are characterised by a special meditative and poetic mood. He creates interfaces between reality, the outside world and the human psyche.

Image Credits

Jošt Franko

Memory without Evidence, 2023/2024

Wallpaper, newspapers. Courtesy of the artist

This work is a multi-perspective exploration of the themes of memory, trauma and existence. Memory Without Evidence is the title of a newspaper published by the artist, which was created as part of a series of workshops and dialogues with displaced persons. It tells the often traumatic memories and stories of people who have fled to the European Union via the Balkan refugee route. For many of those involved in creating the newspaper, the struggle for their existence did not end when they reached the longed-for safe harbour of Europe.

Jošt Franko’s work retells the stories of overlooked and marginalised groups and individuals. He develops his research-based conceptual art practice through the medium of photography. He explores the relationship between personal and collective memories, particularly in relation to war, systemic violence and social injustice. One focus is on the fragility and subjectivity of memory: Who has power over personal (often undocumented) memories? What influence do power structures and ideologies have on collective memory?

Image Credits

Gabriela Golder

Conversation Piece, 2012

3-channel video installation (HD), 19’30’’. Courtesy of the artist

Gabriela Golder’s Conversation Piece shows a reading situation: two young girls read the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1848) together with their grandmother. The girls try to understand the text. They ask questions about contexts, phrases and words that are too complex or unfamiliar to them. Through their insistent questioning, the manifesto is casually deconstructed: What is an oppressor? What is oppressed? What is a revolution?

The work is designed as a triptych and plays with historical references, as reflected in the title of the work and in the design of the space. A conversation piece is a traditional genre of painting that shows people in everyday spatial situations. Today, the term usually functions metaphorically as an invitation to conversation. Golder hijacks the format in a search for traces of the personal and national past—the individual and collective traumas of the military dictatorship in Argentina. The grandmother in the video is the artist’s mother, who was an activist in the Argentinian Communist Party; the two girls are her granddaughters.

Golder’s works are situational negotiations that explore how traumatic memories can be passed on and dealt with across generations—or sometimes remain unspoken. ‘Children can deconstruct the world through a reading that does not continue undisturbed, but has mistakes, cracks, and that creates space for questions,’ says the artist. At the same time, Golder addresses the feminist sharing of information, which not only serves to impart knowledge but also has an emancipatory effect. She thus creates a platform that encourages individuals to question social structures and to work for social justice.

Image Credits

Cristian Inostroza

To Set Free / Liberar, 2019

Coins on pedestal, Video, 08’07’’, Courtesy of the artist

The 100-Chilean pesos coin currently in circulation in Chile has the following features: the obverse shows a Mapuche woman in the centre of the coin, surrounded by the inscriptions ‘Republic of Chile’ at the top and ‘Pueblos Originarios’ at the bottom; the reverse shows the national coat of arms, the year of issue, the number 100, the word ‘PESOS’ and two surrounding laurel branches. Its design was put into circulation in December 2001.

Cristian Inostroza’s work is an artistic intervention in the cycle of currencies and fluid standards of value. Using the everyday object of a 100-pesos coin, the artist examines the effects of repressive power structures on the universal human need for freedom and self-determination. His work explores the social unrest and policy of militarisation in Chile since 2019. At the centre of the installation is a video, which is accompanied by a sculptural accumulation of damaged coins in the exhibition space.

Described as peacemaking for Araucania, the video is a kind of tutorial on the gestural liberation of the Mapuche woman from her oppression – from the 100-pesos coin. The Mapuche, the largest indigenous population group in Chile, now make up around ten per cent of the total population, but only have around five per cent of their original territory. For decades they have been fighting for cultural recognition and against the socio-economic disadvantages they experience, particularly as a result of government megaprojects in their territories.

In his works, Christian Inostroza often addresses the psychological and social constraints and effects of political and historical power structures, especially on individuals.

Image Credits

Grada Kilomba

18 Verses, 2022, 18 charcoaled wooden pieces

18 charcoaled wooden pieces, engraved poem, hand painted with gold leaf, fabric, 8 channel sound installation, 30’. Private Collection

18 Verses is a space and sound installation by Grada Kilomba and the second part of a trilogy.

The installation consists of 18 pieces of charred wood with fragments of poetry wrapped in black fabric and sound. It shows the silhouette of a shipwreck as a symbol of displacement, systemic racism and global immigration policies.

18 Verses is based on a poem by the artist that links the past, present and future. The implied shipwreck relates to the water and boats once used in the slave trade and which today form part of the escape routes across the Mediterranean. The wooden blocks were subjected to a traditional burning process, which in its performance of fire and water resembles a process of death and rebirth. For the artist, the material has a poetic, almost sculptural movement – it becomes black water and an embracing Venus. The sound composition was in turn recorded using a special vocal technique with musicians from Cape Verde. They tell a story of historical repetition, of grief and sorrow.

Grada Kilomba’s works are a practice of decolonial storytelling. In her multimedia work, the Berlin-based Portuguese artist scrutinises concepts of knowledge, power and cyclical violence based on themes such as memory, trauma, self-perception and post-colonialism.

Image Credits

Daria Koltsova

Tessellated Self, 2023

Stained-glass installation, 315 cm x 690 cm x 10 cm. Courtesy of the artist

This glass work refers to the famous constructivist Derzhprom building (Palace of Industry), which was built in 1925-1928 in Kharkiv as a ministry building and became a landmark of the city, but also a symbol of Bolshevik power in Ukraine. Tessellated Self reflects on the question of Ukraine’s cultural heritage and ways to preserve it in times of war. The artist uses glass as a medium of protest against indoctrination and propaganda in art. The glass wall is also a reference to the art form that was common in Soviet palaces, the seats of power structures, during the Soviet era.

After Ukraine’s decommunisation in 2015 and especially after Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine, the issue of cultural heritage has become particularly problematic. The material also emphasises the fragility of our surroundings. The many individual glass fragments are a symbolic reference to Ukraine’s turbulent history. Having grown up in Kharkiv, on the border with Russia, the artist also uses this work to explore her own intrapersonal identity conflicts.

Image Credits

Goshka Macuga

The Nature of the Beast, 2009 Installation

Installation, mixed media: tapestry, wooden and glass table, leather and metal chairs, bronze sculpture on wooden plinth. Courtesy Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Torino / on loan from Fondazione per l’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea CRT

Goshka Macuga’s multi-part installation is a critical examination of the symbolic power of art and its political instrumentalisation. The artist draws on the history and symbolism of Pablo Picasso’s monumental painting Guernica.

Picasso created Guernica in 1937 as a reference to the bombing of the Basque town of the same name by German-Italian air force troops during the Spanish Civil War. The work was presented at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1939 and quickly became an artistic and political statement against violence, war and fascism. A tapestry reproduction of the painting – commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller in 1955 – has hung in the entrance area of the UN Security Council in New York since 1985. When the then US Secretary of State Colin Powell gave a speech about the attack on Iraq in the UN Security Council on 5 February 2003, the tapestry was deliberately covered with a blue curtain.

The fact that Guernica has served as a ‘backdrop’ for politics since its creation is taken up by the artist in her installation. The large-scale tapestry was created on the basis of a press photograph taken during Goshka Macuga’s exhibition at London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 2009. Prince William held a press conference in the exhibition space at that time. Macuga chose to preserve that event in the form of a tapestry to also express her critical self-reflection on her own artistic strategy. The artist demonstrates how easily an artwork may be appropriated, also as a representation of power.

A round conference table is positioned in front of a replica of the tapestry, serving as a discursive podium. Groups and associations are invited whose values correspond to the ethics of the art installation and its commitment to world peace. The exhibition space becomes an activatable, discourse-promoting meeting place, which enables the exchange of ideas and perspectives on issues of peace, violence and global justice.

Image Credits

Daniela Ortiz

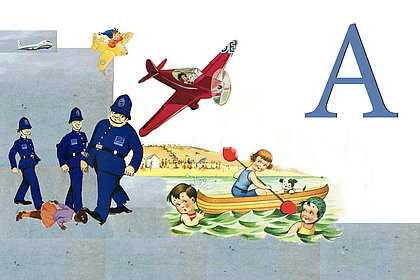

ABC of Racist Europe, 2017

Colour print, digital collage, Book: 21 x 21 cm, Letter: 30 x 30 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Daniela Ortiz’s ABC of Racist Europe is a critical examination of European colonial history, (institutional) racism and the persistence of post-colonial structures in Europe. The book examines the connections between today’s migration control system and colonialism by reinterpreting terms and placing them in a critical context. Stories and mechanisms of oppression, discrimination and resistance are told and visualised through the individual letters of the alphabet. The design and illustrations, which deliberately take the form of a children’s book, serve as a provocative artistic device to vividly illustrate the systemic violence and historical repression that characterise Europe in relation to colonialism and racism.

Image Credits

Ahmet Öğüt

Monuments of the Disclosed, 2022

9 digital monuments dedicated to nine historical whistleblowers: Bunnatine (Bunny) Greenhouse, Marsha Coleman-Adebayo, Marlene Garcia-Esperat, Mona Hanna-Attisha, Kimberly Young-McLear, Philip Saviano, Karen Silkwood, Aaron Swartz, Li Wenliang. Commissioned by Artwrld. Courtesy of the artist

Inspired by the courageous actions of numerous ‘truth-tellers’, Ahmet Öğüt created the Monuments of the Disclosed in collaboration with Artwrld – a series of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) in the form of digital monuments to whistleblowers. These individuals, who have often faced great personal sacrifice in order to stand up to systems of power and expose injustice, fraud and abuse, tend to go unrecognised.

The question of who should be honoured with a monument, and why, runs through history – and the answers vary according to geographical and historical context. Öğüt develops these monuments in the digital realm, accessible by scanning a QR code so that they can be viewed in augmented reality via mobile devices. In this digital sphere, the busts of the whistleblowers hover above their pedestals – fragile and torn, in contrast to the stable monuments we know from the real world. Each monument is dedicated to a person who has stood up against an all-powerful system.

In his multidisciplinary and conceptual practice, Ahmet Öğüt challenges our perceptions and perspectives on monuments and heroism. Criticism and humour combine to create a powerful reflection on human courage and resistance. In the installation shown at the Kunsthaus, the Monuments of the Disclosed are present throughout the building in the form of shadows. Sometimes they are not visible, but their invisible presence bears witness to the enduring human courage and unshakeable belief in humanity.

To access the experience below, use your phone to scan the QR codes

Image Credits

Erkan Özgen

Wonderland, 2016

Single channel video, colour, sound (stereo), 3’54”. Courtesy of the artist

In much of his work, Erkan Özgen engages with the migrant crisis, which he recognises as one of the greatest humanitarian emergencies of our time. He gives voice to the stories of the people he meets, some of whom he befriends, in an approach that is deeply intimate and sensitive, and which reveals the profound trust that the artist has built among the people or communities with whom he works.

His work Wonderland tells the story of 13-year-old Muhammed, who has experienced extreme violence. Muhammed and his family fled the Syrian city of Kobanê, which was heavily besieged by ISIS in January 2015. They crossed the Turkish border and found refuge in Derik, Özgen’s hometown in southeastern Turkey. It was here that Özgen got to know the boy. Muhammed is deaf and communicates only through gestures. Working closely with Muhammed’s family, Özgen recorded the boy’s experiences.

In Wonderland, Özgen explores the limits of language and questions how words can suffice to express experiences that are foreign to us – especially traumatic experiences of war and suffering. The work thus conveys a profound message against war and violence.

Image Credits

Hannes Priesch

How to March, 2024

Video, ca. 22 min, metal grid, organic material

How to March is a collage of military and state representations of mass aesthetic that is transmitted through organisation, synchronisation and control of single bodies. The dream of a total state is always a homogeneous and servile mass that can be controlled and used, representing the fight against chaos. The state parades and marches are a direct manifestation of that desire. Priesch is very much engaged with the topic of ‘we’, how ‘we’ is formed, but also how ‘we’ is maintained through the different rituals and ceremonies. In many of his previous works he explores the marching and assembled bodies, regalia and costumes at the parades and meetings of marching bands almost through an ethnographic lens.

Image Credits

Monira al Qadiri

Crude Eye, 2022

Single-channel video, sound, 10’. Commissioned by Blaffer Art Museum and the Cynthia Woods Mitchell Center for the Arts at the University of Houston. Courtesy of the artist

This dream-like film blurs reality with speculative memory – we are unable to tell if this is a real place or a fantasy. Following the absorbing camera work, the viewer moves through a glowing industrial architecture at night while a haunting narrator's voice recites a poem about a place we cannot define.

Crude Eye draws on the artist's childhood memories of growing up near an oil refinery in Kuwait, where she invented stories for the industrial structures in the distance as she drove past: about a metropolis full of lights, fire, smoke and towers, ‘filled with beings and phantoms from another world’. Kuwait is a relatively ‘young’ epicentre of oil production and refining. In the film, Monira al Qadiri turns her childlike vision of the distant landscape into a glowing topography of a magical kingdom, which at the same time has something threatening about it. Since filming in oil refineries is strictly forbidden, the artist built a miniature model in her studio, which she filmed for this film and supplemented with lines of poetry about a morbidly mystical place.

Monira al Quadiri regularly makes the social and political history of oil extraction and energy dependency the subject of her work. The aesthetic language she uses is alluring and binds us into a relationship exposing the horrific beauty of oil, which can be also read as a symbol of power. The film is an artistic attempt to ‘reconcile a sense of childlike wonder with the toxic environmental destruction that the refinery inherently represents.’ (Monira al Qadiri)

Image Credits

Zanny Begg and Oliver Ressler

Anubumin, 2017

HD-Video, 18’. Courtesy of the artists

Anubumin shows poetic images of the Pacific island of Nauru, which has a population of around 10,000, while visually connecting these with statements from Australian whistleblowers. In an interview-like format, they reflect on the gaps and missing chapters that characterise both the history and the current situation of the island and its inhabitants. The title of the work means ‘night’ in the language of Nauru and refers to the metaphorical darkness associated with the island’s past and present.

Until 1980, phosphate was mined on Nauru and exported to Australia, rendering large parts of the island uninhabitable and infertile. In the 1990s, Nauru became a centre for money laundering. Today, it is home to an Australian offshore refugee centre that has been repeatedly criticised internationally due to the poor conditions there. Access to the island is highly regulated and limited in order to maintain control over reporting and glimpses into the workings of the camp. Another current threat to Nauru is the steadily rising sea level, which endangers the island and its future.

Zanny Begg and Oliver Ressler create a dystopian image of a place where humanity is pushed to its limits. Four whistleblowers – doctors and nurses who have worked in the offshore detention centre – report on the institutionalised human rights violations that take place there on a daily basis. The detention centre has become a symbol of the dehumanisation of today’s political and economic refugees. At the same time, Begg and Ressler raise the disturbing question of whether the people guarding the refugees today might themselves become tomorrow’s climate refugees.

Image Credits

Anna Zvyagintseva

The Cage, 2010

Textile object, 190 cm x 220 cm x 90 cm. Courtesy Collection M HKA / Collection Flemish Community

The Cage is a structure made of fabric in the original size of a standard cage for defendants in the Ukrainian courtroom. The work refers directly to the prosecution of social activists in Ukraine. Anna Zvyagintseva created it in 2010 in response to the political abuse of the Ukrainian legal system and the prosecution of three members of Hudrada – a curatorial group to which she also belongs – for their social activism.

Current interpretations of the work have shifted due to the developments in Ukraine, which since 2014 has been in a state of almost permanent conflict that further escalated in 2022. While in 2010 the knitted poles of the cage served as a metaphor for lost and stolen time within the judicial system, for the defendants and public representatives who spent hours at court sessions making the machinery of justice transparent, today the cage also becomes a symbol of contradictions between freedom and repression, strength and fragility. The chosen fragile material and the feminist gesture of knitting emphasise the increasing fragility of the legal structures and democratic systems surrounding us, with the call to enforce and protect the idea of the rule of law.

Image Credits

Lukas Marxt

Fat Man 1:1, 2023

Sculptural installation: styrofoam, fibreglass, folders, found parts of a Fat Man dummy-bomb and an assembled accurate 1:12 scale replica of Fat Man, upscaled 24-piece assembly kit of the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki. Courtesy of the artist

The human fascination with destruction and the instruments of violence is complex and controversial. Some objects that symbolise power and violence exert a particular attraction and are collected not only for educational reasons but also because of their symbolic meaning. Weapons and tools of destruction are often the subject of admiration and longing because they are charged with a special symbolic power.

Lukas Marxt spent seven years exploring the Salton Sea and surrounding areas in Southern California—a place where atomic bombs were tested during the Second World War. His work combines questions about the exploitation of nature, human violence and history. The resulting extensive project includes video material, objects and archive documents.

Fat Man 1:1 is part of this research-based work and shows an enlarged model of the atomic bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki in 1945. However, the model is not based on the real bomb, but on a military souvenir created from leaked information and speculation. It was reconstructed by John Coster-Mullen, a nuclear archaeologist, industrial photographer and truck driver whose research has enabled a public record of the construction of the first atomic bombs. Marxt’s work questions our collective memory and fascination with the destructive power of such weapons.

Image Credits

Ala Savashevich

Sew on your own, 2022

Chainmail apron, metal structure (stell), 80 x 25,5 x 40 cm. Courtesy of the artist and eastcontemporary, Milan

The human body, and particularly the female body, was and is still often the object of disciplinary measurements and submitted to obedience. Fashion and clothes offer a good reflection of this, particularly female uniforms. Sew on your own explores the personal experience of the artist and her education in a Belarusian school, where girls were still taught how to do housework, sewing, making handicrafts and ornaments. Ala Savashevich is interested in both the protective function of clothing and its role as an instrument of oppression. In her practice she examines collective memory and identity formation, in particular gender roles in social systems with the experience of authoritarian rule. Aprons (white for festive occasions, black for everyday use) were a constant feature of the Soviet school uniform. Made from a standard pattern, they had a special function: to symbolise cleanliness and diligence. The formal starched white version was designed to emphasise the compliance and helpfulness of the schoolgirls who wore it.

Made by hand from thousands of braided metal parts, the apron stands for the overwhelming burden of the ‘image of femininity’ ascribed by society. It is, however, also a symbol of resistance against the violent, patriarchal ‘normality’ that prevails in many places in social institutions such as the family or school.