In works by Albert Oehlen, Salvador Dalí, Arnold Böcklin, Christian Ludwig Attersee and Karel Teige, mythology becomes a defining constant as an old principle for organising the world of idols, but it is always the artist's personality, regardless of its fragile and questionable status, against which all the possible myths are measured.

As an artist, Albert Oehlen eludes pigeonholing in the highest degree and with extreme consistency. In the early 1980s, his paintings became known in the context of a re-evaluation of painting as such, at the same being seen as an explicit antithesis of the movement of the “Neue Wilden” (New Fauves).

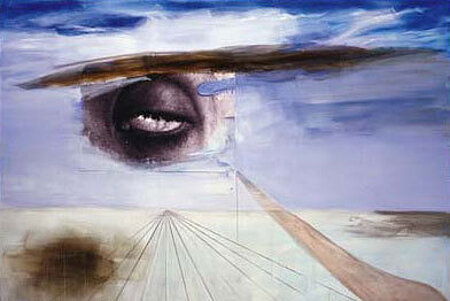

Among the leading reference figures of modernism there are those that the traditional view has made heavy weather of, almost as if in their contradictoriness they lay athwart the official story of art. Salvador Dalí was one such. The wilfulness he expressed in his work and way of life ran contrary to popular images, seeking to create a synthetic ideal of the artist based on a bizarre unity of art and life. This was inevitably grist to the mill of an artist who himself intensely experienced the end of modernism and in his work took up the contradictions that resulted therefrom. An additional factor was that the art of Oehlen’s generation was notably and consciously preoccupied with popular culture, and in this context Dalí is also interesting as a ‘pop star’ before his time – one who as a mythmaker tailored the scenarios of art and society wholly to fit himself, thereby causing an arbitrary displacement in whole systems of references.

Focusing on these two art personalities, we are trying to trace the relationships between art and mythmaking and, consequently, to identify the place of a modern mythology in art too.