Easter and the often traditional Easter customs associated with it are very important in many of Austria's federal provinces. What do people celebrate at Easter? When is Easter Sunday? Why are Easter eggs colourful? Here we have summarised typical customs, but also some perhaps forgotten Easter customs to get you in the mood for Easter.

Customs and traditions aroung Easter

Easter: the "Palmbuschen", the Easter egg and the consecrated meat

Image Credits

Palmsonntag

Easter is the Christian celebration of the resurrection. Easter customs begin with the commemoration of Jesus' entry into Jerusalem on Palmsonntag. As a sign of his kingship, the people cheered him on and strewed palm branches for the one coming to Jerusalem (e.g. John 12:13-15). Palm trees were honoured as sacred trees in many places and were sacred to Apollo in Delos, for example. In the Mediterranean region, they have always been regarded as a symbol of life and victory, and in Israel in particular as a symbol of independence and the victorious king. In Austria, various regional "Palmbuschen" are tied with seven or nine different plants, decorated with ribbons, in some places attached to poles up to eight metres long, and carried to the palm consecration. Small crosses are made from the blessed palm branches, which are attached to the stable door as a sign of blessing, burnt in the pan when burning incense or stuck in the ground to prevent mischief.

Image Credits

Gründonnerstag

Gründonnerstag is the day before "Karfreitag" and is one of the three Holy Days in the narrower sense. The so-called Triduum Sacrum (or Triduum Paschale), the celebration of the three days of Easter (Karfreitag, Karsamstag and Easter Sunday), begins on the evening of Gründonnerstag with the commemoration of the Last Supper. As a commemoration of the Last Supper and the associated institution of the Eucharist by Jesus Christ himself, Gründonnerstag has a high status in the liturgy. Eggs laid on Gründonnerstag, the "Antlasseier", were once considered to be particularly healing, with the green painted Gründonnerstag egg being believed to ward off injuries, the red Karfreitag egg to protect against fire and the blue Karsamstag eggs to help in the event of flooding. On the evening of Gründonnerstag, at the hour of Christ's agony, the farmer went to his land to "Baumbeten" (pray to the tree), knelt down under a tree and prayed with outstretched arms.

Image Credits

Karfreitag

On Karfreitag, when church bells were no longer allowed to ring, the "Ratschenkinder" went from house to house in the morning, at midday and in the evening, in some places announcing the full hours. On Karfreitag, work in the fields was suspended from nine o'clock in the morning. Instead, the house and yard were swept and cleaned spick and span. "Ratschen", also known as "Leiern" or "Kleppeln", is a custom that is practised during Holy Week. According to tradition, the bells are silent from Karfreitag until the Easter evening, as the festive sound of the bells would be inappropriate at the time of Jesus' death. In the past, children with wooden instruments - "Ratschen" and "Klappern" - used to parade through the villages to remind the faithful of the devotions and prayers with various sayings, and in some places also to announce the full hours. On Karsamstag, they go to the houses to collect their reward - eggs, meat or money. There are various forms of these noisemakers. The "Ratschen", which already existed in the Middle Ages, consist of a board with a handle that is struck by a small hammer that can be moved by a joint. "Ratschen", the more familiar form today, are rollers connected to a handle, over which a movable frame with several sound boards rumbles and makes a rattling noise. "Ratschen-walking" is experiencing a new upswing these days.

Image Credits

Karsamstag

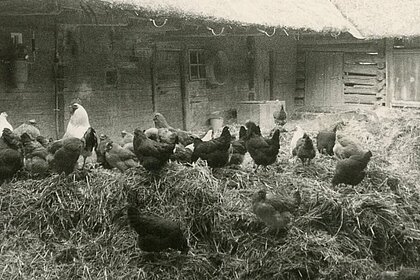

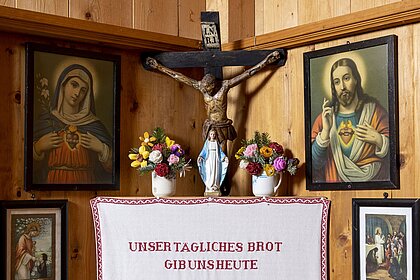

Karsamstag (old-German kara ‘lamentation’, ‘sorrow’, ‘mourning’) is the last day of Holy Week and the second day of the Easter Triduum. It is also known regionally as Silent Saturday. Christians commemorate the burial of Jesus Christ on this day. On Karsamstag, the "Ratschen-Kinder" went into the houses to collect their wages - eggs, meat or money. Throughout the year, care was taken to keep the hearth fire safely overnight and to ensure that it did not go out. However, once a year they deliberately let it go out, on Karfreitag. On Karsamstag morning, the kdis ran to the church to fetch the "Weihfeuer" (bonfire). They hurried home with it as quickly as possible, as the first to arrive at the farm with the fire received special gifts. The Easter food was cooked with this fire. Smoked meat, bread, salt and eggs were carried to church in a consecration basket under an embroidered blanket called a "Weichatuch" and blessed. This consecration cloth was once not allowed to be washed or used for any other purpose. In summer, it was hung on the fence to ward off storms.

Image Credits

Ostersonntag

In the night from Karsamstag to Ostersonntag (Easter sunday), the mourning over the death of Jesus turns into the joy of his resurrection. On Karsamstag, people attended the fire consecration early in the morning and brought home the blessed fire with a smouldering birch sponge. This was used to light the wood for cooking the sacred meat. Easter fires were lit and firecrackers were fired as a sign of joy. The highlight of the Easter period was the resurrection celebration, which everyone had to attend in new clothes. The farmer was obliged to give the maids and servants a new Sunday robe. The decorated or coloured Easter egg was a gift from the parents and godparents to the children and servants; it was a gift of friendship, mint and worship. Girls gave their sweetheart a red egg, and a gingerbread heart was given in return on church day. Findings show that the early Christians of Mesopotamia already dyed eggs, preferably in the colour red, which is reminiscent of the blood of Christ and is considered the colour of life. There were practical reasons why the eggs were coloured differently. Due to the Catholic Church's commandment to fast, eggs were not allowed to be eaten alongside meat from "Aschermittwoch" until Easter sunday. To prevent the eggs produced during the forty-day fasting period from going bad, they had to be preserved. To do this, they were first boiled in water.To distinguish the boiled eggs from the fresh, uncooked eggs, plants were added to the boiling water to colour the eggs differently.This meant that there were different coloured eggs on Easter sunday.

Image Credits

Rare customs at Easter

"Eierscheiben": A slide made from two boards was quickly built. The children let the eggs roll down this slide over a slope that was not too steep. They then ran in a wide arc to the right or left, depending on where you pointed the tip. The next person had to try to hit the egg, then it was theirs. Otherwise it also remained lying there until one was hit.

Another custom was to damage the egg shell with a coin in a well-aimed throw. If it failed, the opponent got the coin.

„Ins Grean gehen“: On Easter sunday, it is customary to bless the fields, a custom known as ‘going into the fields’. The farmer goes out into the fields with his people and, while praying silently, palm branches and logs, which were lit during the consecration of the fire on Karsamstag, are put into the fields, sometimes also bones from the consecrated meat.