Collectively wanting art – theory and practice. Numerous subsidiaries of a diverse range of store chains along the Ennstal Highway make the shopping-hub city of Liezen an exemplary terrain for the commercialization of public space. After 1947 the capital of Styria’s largest district grew rapidly, and in the 1970s urban planners decided to construct a new main town square. Now, in the historic city center around the parish church small trade and commercial enterprises are increasingly fighting for economic survival, and a number of business premises stand vacant. In 2010, local business owners formed the Interessengemeinschaft Kirchenviertel (church district interest group). In their search for new strategies to upgrade and revitalize the location, art soon became a focus. The suggestion was made that reproductions of artworks on tarpaulins could be hung on the building façades, and the group made contact with the Institute for Art in Public Space Styria.

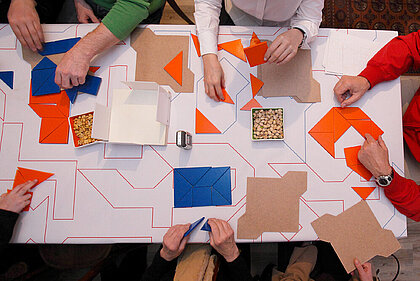

Art as a motor of the development of concrete urbanistic perspectives: The urban interventions by Barbara Holub and Paul Rajakovics come into play where conventional urban-planning instruments run up against their limits. Under the label transparadiso, Holub and Rajakovics develop new tools and strategies “in order to reflect on urbanism as a complex social concern that includes social aspects beyond neoliberal economic activity.” An “outdoor gallery” as a marketing tool on the one hand and Tools for Direct Urbanism on the other – bridging such diverse concepts was a challenge. Nevertheless, both the interest group and the artists proved amenable to the process of collaboration instigated and accompanied by the institute. Proceeding from the conviction that, rather than being instrumentalized as a problem-solver, art can and should take the role of a co-combatant, Holub and Rajakovics confronted the interest group of traders and real-estate owners with an idea that countered the neoliberal commodification of public space by aiming to rediscover and propagate the value of commons. transparadiso deployed the tangram game as a vehicle for the theory of sharing and participating and at the same time defined a new sphere of application in the context of establishing a commons community: collective art collecting.

A precisely defined sequence of game and discussion phases, including content inserted by transparadiso, was designed to generate communication around the theme of communal (economic) action, to expand the membership of the interest group Interessengemeinschaft Kirchenviertel to form a larger, reconceptualized community working in the public interest, and to activate the transformative power of commons. The goal: “To read Liezen in a new way via the collective urban experience.” A pavilion installed in public space that initially served as a storage facility for large tangram pieces constituted a central marker on the envisioned route to a new urban identity. The concept saw those purchasing the objects as acquiring a share in a collective artwork – and assuming responsibility for furthering the process of participation. The proceeds from the sale were envisioned as providing the financial basis for subsequent uses of the (empty) pavilion initiated by local residents and the tangram pieces as remaining in private collections until the commons participants collectively decided to meet again for public games. As research quickly showed, access to the commons discourse was facilitated by a direct reference to the location: a meadow in the church district, the former garden of a private villa, had been planted with apple trees following the Second World War and transformed into a public city park. One result of the commons project was to restore this common land to the collective consciousness of local citizens. The ideal location for the pavilion was found.

In the course of the first, well-attended round of games held in an empty shop – made available by the interest group and thereby facilitating the regular presence of transparadiso in Liezen – the circle of competitors, as hoped, increased: the organization Jugend am Werk (a training center for youths disadvantaged by labor-market policies and daily workshop for people with special needs) produced small- and large- scale tangram sets in the colors of traffic blue and traffic orange, and the director of the city marketing and tourism office and the operator of the public radio station FREEQUENNS threw their weight behind the project. Then the tangram players moved to the city park, where the pavilion was erected, referring in formal terms to the modernist architecture of the ensemble of buildings on the town’s main square. The pavilion, filled with tangram pieces, was presented to the public by way of a festival and a tangram competition. However, despite its low cost, the sale of the limited edition did not meet expectations. The project dynamic and the involvement of a wider public proceeding from the pavilion as a starting point have deteriorated – in part because of a lack of support for the projec by local politicians. To be continued?

In participation-oriented projects, the creation of intersections between different levels is a decisive factor: one level that enables those initially encountering an expanded concept of art and new ideas to actually “play along,” and another that does justice to the necessarily individual and potentially oppositional artistic claim and larger theoretical contexts. The task of forging this intersection is inseparably connected with the question of operational spaces, including the temporal aspect, and the density of the pattern of predefined rules and expectations with regard to (visible) results. The possibility that the way an idea develops can diverge from what has been meticulously planned beforehand cannot be excluded in the case of projects such as Commons kommen nach Liezen (commons come to Liezen), which, as a process, as a conceptual and action space, intervenes directly in people’s living space.

Birgit Kulterer